Although it has come under recent criticism from linguists like Geoffrey Pullum, The Elements of Style by Strunk and White is often cited as the classic text on writing English prose. One of the most famous imperatives from the book is:

Omit needless words.

If that’s a bit too sparse for your ears, pull up a chair and luxuriate in this extended description of the principle:

Vigorous writing is concise. A sentence should contain no unnecessary words, a paragraph no unnecessary sentences, for the same reason that a drawing should have no unnecessary lines and a machine no unnecessary parts. This requires not that the writer make all his sentences short, or that he avoid all detail and treat his subjects only in outline, but that every word tell.

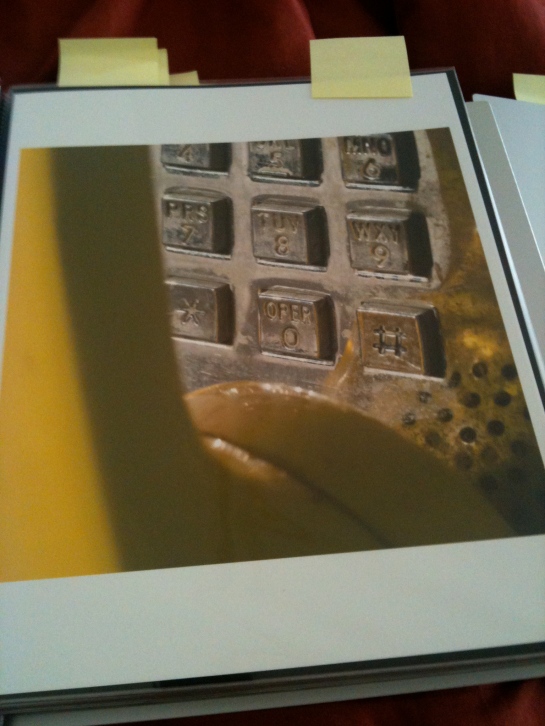

Here is the image that best captures my response to the above:

Yes, I’ve come to believe that “Omit needless words” is in fact a recipe for needless suffering and confusion.

The principle sound perfect. If a word is unnecessary, then by the very definition of unnecessary, we can strike it out with no adverse effect, so let’s do that! Who but a fool would decide against economy and simplicity in writing?

The problem is that it’s hard to judge whether a word is truly needless. Sentences are complex beasts and so are the minds we use to interpret them. The logic that beckons us to remove a word is often based on an incomplete understanding of how words interact. As we will see, words that appear like dead weight can contribute in very significant ways to the meaning and impact of a sentence. Keep cutting out the “unnecessary” words and you might be left not with a glistening core of meaning, but with a skeleton that doesn’t express it.

Let’s look at the examples Strunk & White use to illustrate their maxim. They tell us the phrase “he is a man who” should always be compressed to “he.” So let’s consider a simple sentence that perpetrates the excess in question:

He is a man who steals.

If we are to omit needless words, we should rewrite this as:

He steals.

At first glance, it looks like we scored. The first word tells us the sentence refers to a man, so “is a man who” can be axed. The meaning stays the same and we’ve reduced our word count.

Here’s where I raise my hand as a pesky student. Herr Professor, uh, don’t those sentences have different connotations?

To my ears, “He steals” is a neutral statement. It informs us about the man’s actions without implying a judgement about his character. This guy could be Robin Hood for all we know.

But “He is a man who steals” puts us in the mood for judgement. The apparently needless verbiage “is a man who” is actually critical: it invites us to think about what kind of man this is. The idea that men belong to different categories is invoked here, but not in the shorter phrase. If our subject is the kind of man who steals, he’s probably not a good man — safe to assume?

Let’s take another example:

His story is a strange one.

Strunk & White prefer:

His story is strange.

Again, it seems virtuous to remove the excess, but in doing so, we change the connotation.

“His story is strange” suggests that what happened to the man is strange.

“His story is a strange one” suggests that these events make a strange kind of story.

It is like the difference between getting run over by a hovercraft (case 1) and waking up to find you’ve become a cockroach (case 2). Anyone could get run over by a hovercraft: unlikely, but possible. And yet to wake up as a cockroach would be positively Kafkaesque!

Now let’s take an example that illustrates “Omit needless words” together with “Put statements in positive form.” Strunk & White tell us to replace:

the fact that he had not succeeded

with

his failure

Indeed, we are supposed to excise “the fact that” wherever it occurs. But wait a minute, are those phrases equivalent? What if the guy in the sentence isn’t ready to give up? It would then be plausible to say:

The fact that he had not succeeded didn’t convince him of his failure.

Of course we could shorten this to:

His failure didn’t convince him of his failure.

But those sentences suggest different things. The first leaves open the possibility that success might lie in the future, while the second suggests that the failure is definitive and the man simply won’t admit it.

So far, we’ve seen how “needless” words can change the rhetorical impact of a sentence by steering us down a different path of interpretation (for example, encouraging us to think about a category — a kind of man or story — instead of a specific instance). Another way “needless” words can affect the rhetorical impact of a sentence is by altering its rhythm. Words that seem needless might actually perform the vital role of keeping the beat. By definition, “prose ain’t poetry,” and yet the experience of reading prose is shaped by the same metrical factors that poets obsess over.

Here are two rewrites that Strunk & White propose, based on the idea that “who is” and “which was” are superfluous:

His brother, who is a member of the same firm

His brother, a member of the same firm

Trafalgar, which was Nelson’s last battle

Trafalgar, Nelson’s last battle

What is the result of cutting those words? When I read the sentences out loud, I find the wordier versions are easier on the tongue. Why? Because “who is” and “which was” function here like pick-up notes in music, preparing us for an accented beat that follows. Take them out, and you bring the stressed words closer together. As a reader, I tend to compensate by leaving a longer pause after the comma, so that the stresses will be better separated, but such a pause can disrupt the flow of speech.

So what are we actually trying to optimize when we cut “needless” words? If we must pay per word, as in print publication where ink and paper are expensive, there’s an economic incentive. But people often assume that reducing word count is more than a way to save money, it’s also a way to save the reader’s time. Fewer words makes for quicker reading. That’s a fallacy.

When I read

His brother, who is a member of the same firm

the words “who is a” roll out quickly and almost bleed into the stressed word “member.” But when I read

His brother, a member of the same firm

the pause I’m inclined to take after the comma is a bit longer than the time it would take me to say “who is.” Without the pickup beats, the rhythmic similarity between “brother” and “member” comes to the foreground and sounds a bit clunky.

In this case, cutting those filler words makes for slightly slower reading.

Reader, I hope I’ve given you some food for thought which might save you from descending into Munchian anguish the next time you sit down to edit your prose, earnestly omitting needless words as The Elements implore, and then wondering what went wrong. Words that seem like slackers might actually be your most helpful friends; omitting them is often needless.