Announcing Canon #87 — “Barite.”

Work on this piece started in a typical way for me. I spent a week exploring various ideas from my canon to-do list, but I couldn’t get any of my sketches to take flight. I kept working through Memorial Day weekend; still nothing. It was hard not to think the long weekend would have been better spent on something else entirely – maybe I should have given up and tried again later? – but I know that every day that seems fruitless is an investment in what’s to come. In a sense, you can’t get something done unless you’re willing to accept the feeling that you’re getting nothing done, and keep going anyway. Finally on Monday evening, I noticed a simple technical option that I hadn’t yet explored in any of my canons. I’ve written a few canons in 3/4 time where the lag is one beat, but I hadn’t written a canon in 3/4 where the lag is two beats (leader starts on the first beat, follower starts on the third beat). Why not? Although Max Reger isn’t my model for canon writing, I notice he used this construct in a good number of his 111 Kanons durch alle Dur und Molltonarten. Ready for something new to work on, I abandoned the other sketches I had been struggling with and started a canon in 3/4 with a two-beat lag.

As with most of my canons, the first step is to create an outline, not one that I like, but one that I love. Why is this step so important? After all, the quality of the outline doesn’t necessarily dictate the quality of the finished piece. It’s totally possible to transform a lackluster outline into a great piece because as you’re working, you can revise the outline or simply throw it away when it stops serving you. The problem for me is that when I don’t start with an outline I absolutely love, it’s hard to find the motivation to keep struggling to reveal its potential. If I do love the outline, then that love propels me: I feel an overwhelming resolve to do whatever it takes to transform the outline into a full piece of music. So while I could probably start with cursory outlines that take a few minutes to throw together, and maybe I’d produce more pieces that way, I’m more inclined to spend hours or days creating an outline that totally captivates me, because once I’m hooked, I’ll never abandon the piece even when the going is rough. You could say I have a kind of perfectionism about my outlines, but I take the view that perfectionism itself isn’t evil: one just needs to be realistic about what one chooses to be a perfectionist about. Outlines are the good things to be a perfectionist about because they’re simple enough that you actually can make them perfect.

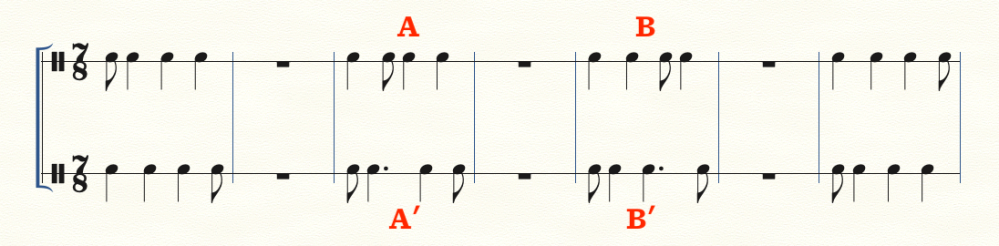

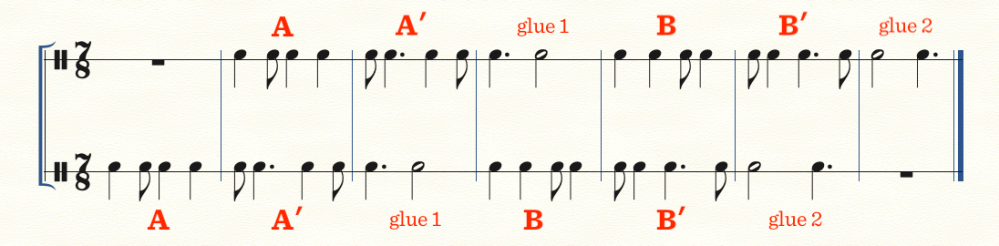

So I started making an outline for Canon 87, and managed to get something I loved. During the outlining stage, I don’t really know what style the piece is going to land in. My outline for Canon 87 was full of unprepared and unresolved dissonances, suggesting it would take on a modern style, but the melodic material was firmly tonal and full of diatonic sequences, and the implied harmonies all seemed to fall within the realm of “common practice.” As I developed the piece, this duality persisted: in a melodic or “horizontal” sense, the piece started sounding like something from the 18th century but in a “vertical” sense it seemed much more modern. Towards the end of the piece, the interval palette becomes more consonant, with more thirds and sixths on measure onsets; the sound is less conflicted in spirit and style. I considered revising the latter part of the piece to keep the style more consistent with the dissonant opening, but I decided instead to embrace the piece’s progression from a dissonant to a more consonant palette, and from a severe to a lighter mood.

To bring the piece to a satisfying conclusion, I knew I’d have to break out of the canon and write some free counterpoint. I was ready for ending to be a struggle as it often is. But then I came upon the idea of having the voices move mostly in parallel at the end (after all, they had established their independence by now, right? What more did they have to prove?). I brought them closer together and had them converge into a unison at the final beat, and that worked.

A few details: the piece uses diatonic imitation at the fourth above. It opens in D minor, progresses to G minor, moves back to D minor, and finally progresses to B-flat major. The imitation is fairly strict, but the bottom line takes various ornaments that the top doesn’t repeat. I chose the name Barite because, for whatever reason, the piece brought the color yellow to mind, and Barite is a mineral that can look yellow when cut as a gemstone (all of the other more familiar yellow gemstone names are taken by now). Unlike many of my pieces, Canon 87 has only one section and doesn’t go through an inversion. (It’s probably possible to get this material to work in an inverted form, but it would take some rewriting, and although I always wish my pieces were just a little bit longer, I think this one reaches a natural stopping point and doesn’t call for an extension.) The piece is based on the simplest of melodic figures: on almost every measure onset, in the bass, you can hear a note, followed by its lower neighbor, and then the note again. I like working with simple figures such as this — I like seeing how much they can do.